Kubernetes Reference

— Kubernetes, DevOps, Backend Development, Complete Reference — 28 min read

Introduction

Kubernetes is a portable, extensible, open source platform for managing containerized workloads and services, that facilitates both declarative configuration and automation. It has a large, rapidly growing ecosystem. Kubernetes services, support, and tools are widely available. Kubernetes is a system for running many different containers over multiple different machines. It is used when we need to run many different containers with different images.

We can work with Kubernetes in development environment using minikube, and in production environment using AWS EKS, GKE or other managed solutions. minikube is local Kubernetes, focusing on making it easy to learn and develop for Kubernetes. It is a command-line tool which sets up a tiny Kubernetes cluster. kubectl is used to interact with a Kubernetes cluster in general and manage what all the different nodes are doing and what different containers they are running. Minikube is used to create and run a Kubernetes cluster in our local machine.

Components of Kubernetes

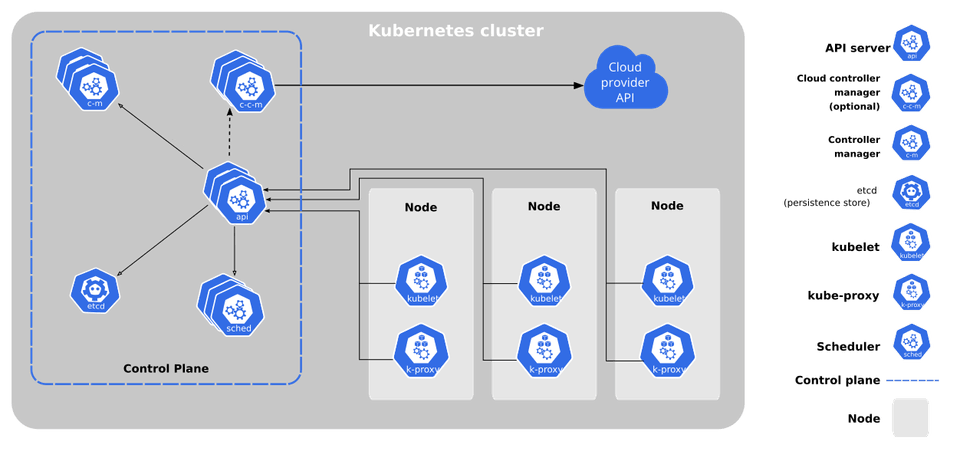

A cluster in the world of Kubernetes is the assembly of something called a master, and one or more nodes. A node is a virtual machine or a physical computer which is going to be used to run some number of different containers. Each node can run different set of containers. All the different nodes created are managed by the master. The master has a set of different programs running on it that control what each of these different nodes is running at any given time. Developers interact with a Kubernetes cluster by reaching out to this master and provide instructions to it (example: to run certain number of containers using a specific image), which are then relayed by master to all the nodes. There is a load balancer outside the cluster which takes some amount of outside traffic in the form of network requests and relay all those requests into each of these different nodes.

The worker node(s) host the Pods that are the components of the application workload. The control plane manages the worker nodes and the Pods in the cluster. In production environments, the control plane usually runs across multiple computers and a cluster usually runs multiple nodes, providing fault-tolerance and high availability.

Control Plane Components

The control plane's components make global decisions about the cluster (for example, scheduling), as well as detecting and responding to cluster events (for example, starting up a new pod when a deployment's replicas field is unsatisfied).

Control plane components can be run on any machine in the cluster. However, for simplicity, set up scripts typically start all control plane components on the same machine, and do not run user containers on this machine.

- kube-apiserver - The API server is a component of the Kubernetes control plane that exposes the Kubernetes API. The API server is the front end for the Kubernetes control plane. The main implementation of a Kubernetes API server is kube-apiserver. kube-apiserver is designed to scale horizontally—that is, it scales by deploying more instances. We can run several instances of kube-apiserver and balance traffic between those instances.

- etcd - Consistent and highly-available key value store used as Kubernetes' backing store for all cluster data

- kube-scheduler - Control plane component that watches for newly created Pods with no assigned node, and selects a node for them to run on

- kube-controller-manager - Control plane component that runs controller processes. Logically, each controller is a separate process, but to reduce complexity, they are all compiled into a single binary and run in a single process.

- cloud-controller-manager - A Kubernetes control plane component that embeds cloud-specific control logic. The cloud controller manager lets us link our cluster into our cloud provider's API, and separates out the components that interact with that cloud platform from components that only interact with our cluster. The cloud-controller-manager only runs controllers that are specific to our cloud provider. It combines several logically independent control loops into a single binary that we run as a single process. We can scale horizontally (run more than one copy) to improve performance or to help tolerate failures.

Node Components

Node components run on every node, maintaining running pods and providing the Kubernetes runtime environment.

- kubelet - An agent that runs on each node in the cluster. It makes sure that containers are running in a Pod. The kubelet takes a set of PodSpecs that are provided through various mechanisms and ensures that the containers described in those PodSpecs are running and healthy. The kubelet doesn't manage containers which were not created by Kubernetes.

- kube-proxy - kube-proxy is a network proxy that runs on each node in the cluster, implementing part of the Kubernetes Service concept. kube-proxy maintains network rules on nodes. These network rules allow network communication to our Pods from network sessions inside or outside of our cluster.

- container runtime - The container runtime is the software that is responsible for running containers. Kubernetes supports several container runtimes: Docker, containerd, CRI-O, and any implementation of the Kubernetes CRI (Container Runtime Interface).

Basic Commands

minikube commands

minikube status- provides information on minikube and kubectl running statusminikube dashboard- dashboard running on port 30000 which provides information on everything inside the Kubernetes cluster. Any edits made to any objects in the dashboard do not persist to the config files, hence it is discouraged.minikube cp <source node name>:<source file path> <target node name>:<target file absolute path> [flags]- copy the specified file into minikube, it will be saved at path in your minikube. Default target node controlplane and If is omitted, It will trying to copy from host.minikube delete- deletes a local Kubernetes cluster. This command deletes the VM, and removes all associated files.minikube ip- retrieves the IP address of the specified node, and writes it to STDOUT. In local environment, the Kubernetes Node VM created by Minikube has its own IP address, which should be used to access any pod / service running in Minikube, not the localhost. Useminikube ipcommand to get this IP address.minikube logs- Gets the logs of the running instance, used for debugging minikube, not user code.

kubectl commands

kubectl cluster-info- provides information on master, KubeDNS statuskubectl apply -f <filename>- it is used to provide a config file to kubectl.applycommand changes the current configuration of our cluster with kubectl. It is also possible to run this command on all YAML files in a directory by usingkubectl apply -f <folder-name>.kubectl get pods- prints the status of all running pods.get pods- specifies that information needs to be retrieved about a running object, and the object type is pods in this case. In the output, underREADYsection, 1/1 indicates that there is one copy of the object running, and desired number of objects running is 1.-o widearguments forget podscommand provides more information on pods, like host IP and node name.kubectl get servicesprints the status of all running services. It doesn't display thetargetPortof services.kubectl get deploymentsprints the status of all deployments, in the output of whichDESIREDandCURRENTrepresents number of desired objects and number of current objects running respectively,UP-TO-DATErepresents number of objects up-to-date with given config file andAVAILABLErepresents number of objects that are ready to receive traffic.kubectl get pvlists out all persistent volumes attached to the Podskubectl get pvclists out all persistent volume claims configured.

kubectl describe <object-type> <object-name>- gets detailed information about an object inside a Kubernetes cluster. If<object-name>is omitted, then it describes all objects having<object-type>. Example:kubectl describe pod client-pod1.kubectl delete -f <config-file>- removes a running object specified by config file that created the object. Deleting objects is an imperative approach in Kubernetes (not declarative).kubectl set image <object-type>/<object-name> <container-name>=<new-image-to-use>- changes a property of an object inside the cluster by specifying the object name, property and the new value that the property should have.kubectl delete <object-type> <object-name>- deletes an object. Example:kubectl delete deployment client-deployment- deletes a deployment.kubectl logs <pod-name>- gets all logs for a pod, if they exist.kubetl get storageclass- lists out all different storage options available in the cluster that Kubernetes has for creating a Persistent Volume.standardis the default option.

Kubernetes Objects

Kubernetes objects are persistent entities in the Kubernetes system. Kubernetes uses these entities to represent the state of our cluster. Specifically, they can describe:

- What containerized applications are running (and on which nodes)

- The resources available to those applications

- The policies around how those applications behave, such as restart policies, upgrades, and fault-tolerance

- A Kubernetes object is a "record of intent" -- once we create the object, the Kubernetes system will constantly work to ensure that object exists. By creating an object, we're effectively telling the Kubernetes system what we want our cluster's workload to look like; this is our cluster's desired state.

Almost every Kubernetes object includes two nested object fields that govern the object's configuration: the object spec`` and the object status`. For objects that have a spec, we have to set this when we create the object, providing a description of the characteristics we want the resource to have: its desired state.

The status describes the current state of the object, supplied and updated by the Kubernetes system and its components. The Kubernetes control plane continually and actively manages every object's actual state to match the desired state we supplied.

Kubernetes expects all images to already be built, which are ready for deployment on to Kubernetes cluster. We have multiple configuration files in Kubernetes, and each of these config files are used to create a different object (which isn't necessarily a container) using kubectl. We have to manually set up all networking in Kubernetes.

Example Object Types include: StatefulSet, ReplicaController, Pod, Service. Objects are essentially things that are going to be created inside Kubernetes cluster to get our application running as expected, and they serve different purposes - running a container (Pod), monitoring a container, setting up networking (Service) etc. The kind keyword in yaml files represents the type of object that should be created.

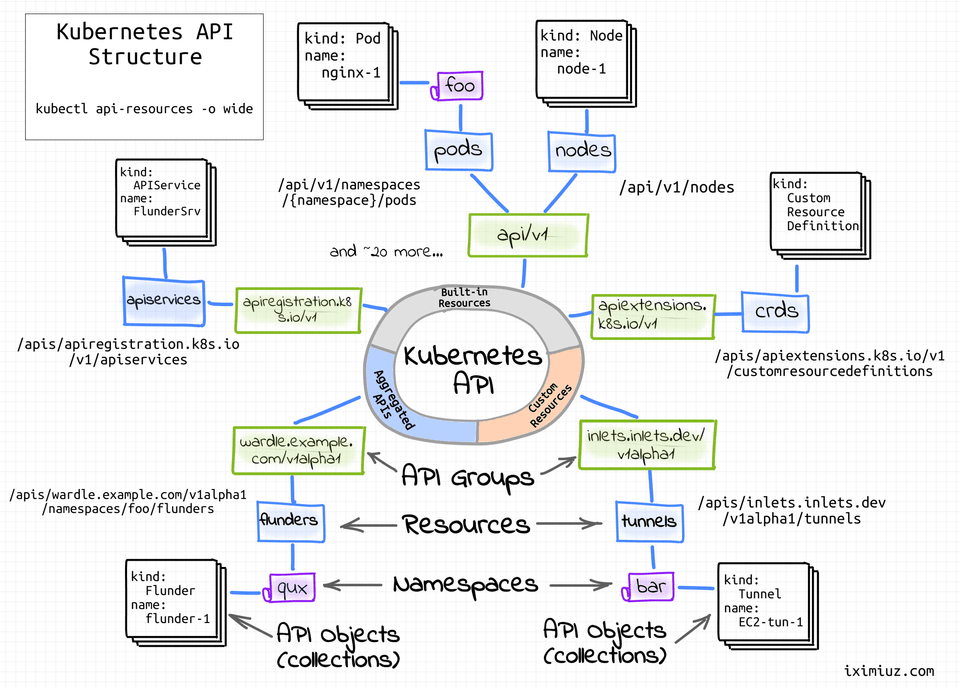

When we specify the apiVersion, it essentially scopes / limits the types of objects that we can specify that we want to create within any configuration file. Each API version defines a different set of 'objects' we can use.

A Pod is a grouping of containers (one or more) with a very common purpose, which runs these closely related containers. It is the smallest thing we can deploy within a Kubernetes cluster, to run a single container. Always group containers in a pod that have a very tightly coupled relationship, and must be running together. metadata is used in kubectl to provide additional information about the object which can be useful in logging. Pod runs a single set of containers, used for development purposes, but not in production. Every single Pod gets an IP address assigned to it that is internal to the VM.

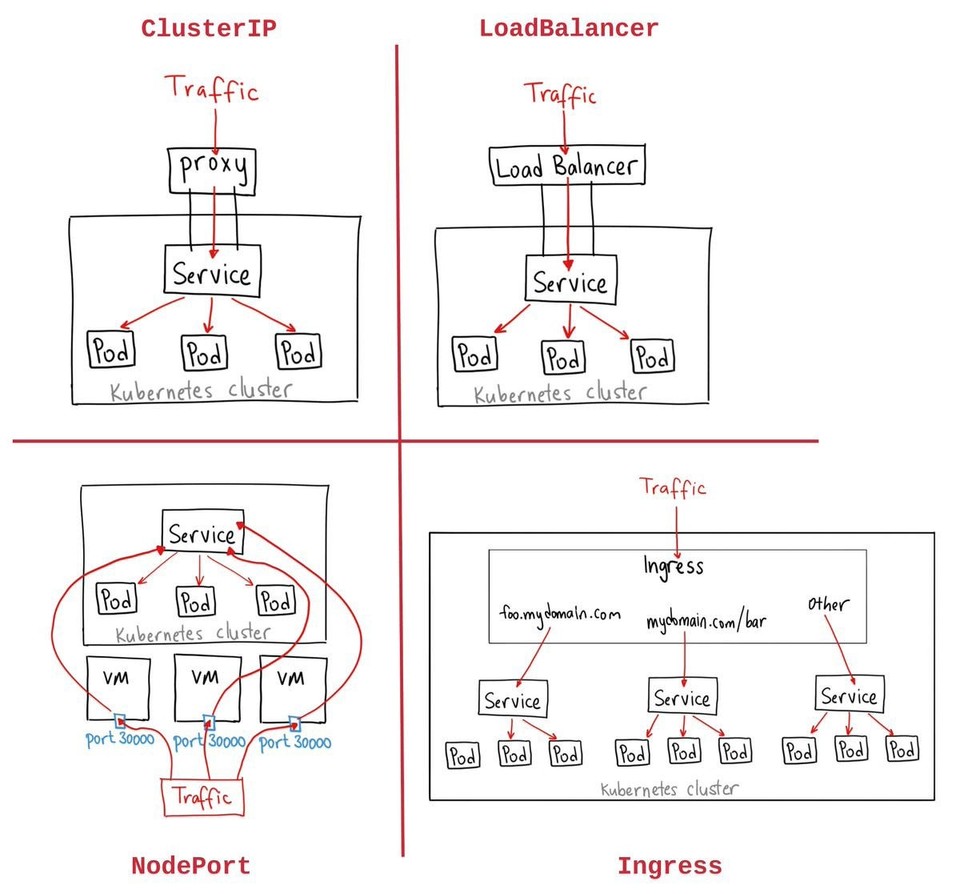

A Service sets up networking in a Kubernetes cluster. There are 4 commonly used subtypes among Services: ClusterIP, NodePort, LoadBalancer, Ingress. The purpose of a NodePort service is to expose a container to the outside world, and it is only good for development work.

A Deployment is a Kubernetes object which maintains a set of identical pods, ensuring that they have the correct config and that the right number exists. Deployment object is also referred to as a type of contoller. A controller is any type of object that constantly works to make some desired state a reality inside the cluster. Deployment runs a set of identical pods (one or more) and monitors the state of each pod, updating as necessary. It is frequently used in both development and production environments. A Deployment consists of a pod template, which is essentially a configuration block which describes pods created by the deployment (ReplicaSets are legacy variant of Deployments).

ClusterIP service exposes a set of pods to other objects in the Kubernetes cluster (but not to outside world), whereas NodePort exposes a set of pods to the outside world. ClusterIP follows the same port nomenclature as NodePort service.

A Namespace is used to isolate the different resources that are created inside Kubernetes cluster. A ConfigMap is an object that holds some amount of configuration that can be used throughout the cluster. kube-system namespace (which is created automatically) contains some objects that make the entire cluster work as expected at an administration level.

Let's consider a container having exposed port 3000 via containerPort option, running in a Pod, which is enclosed and running within a Kubernetes Node (e.g., VM created by MiniKube). Every single node or every single member of a Kubernetes cluster that we create has a program on it called kube-proxy, which is essentially the one single-window to the outside world. Any requests coming in flow through kube-proxy, which inspects the request and decides how to route it to different services or different pods that are created inside the Node. The NodePort service forwards the incoming request from kube-proxy to the exposed port on the running container defined inside the Pod.

Label Selector System is used in Kubernetes to specify which Pod should the Service route the incoming requests. In the provided example configs, the component: web key-value pair under labels allows the container to link to Service with component: web key-value pair in its configuration. The key-value pair can be anything, as long it is the same for both Pod and Service. This system is also used by Deployment to communicate to master to gain control over the objects created by master having the specified key-value pairs. Service watches every pod that matches its selector and then automatically route traffic to it, irrespective of pod deletion and re-creation (resulting in change of Pod's internal IP address).

Master contains 4 programs that control the entire Kubernetes cluster. One of them, Kube API server is responsible for monitoring the current status of all the different nodes inside the cluster and ensure that they are running. It takes in YAML deployment files as input and maintains a table of all objects that are currently running and the objects that need to be run along with the required number of copies of objects. Each node has a copy of Docker running in it, which pulls image from provided docker registry and runs the containers as per the requirements. The Kube API server automatically instructs nodes to restart crashed containers and ensures that the desired number of objects are running.

Each node can run a dissimilar set of containers, depending on the requirements (number of desired objects). To deploy something, we update the desired state of the master with a config file and the master works constantly to fulfill this state. But kubectl apply -f <filename> can only be used to update certain fields like image, but not container ports or other fields.

Sample Configurations

Sample container config (Pod)

apiVersion: v1kind: Podmetadata: name: client-pod labels: component: webspec: containers: - name: client image: someuser/multi-worker # assuming image is on DockerHub ports: - containerPort: 3000Sample networking config (NodePort)

apiVersion: v1kind: Servicemetadata: name: client-node-portspec: type: NodePort ports: # describes all the collection of ports that need to be opened up or mapped on the target objects - port: 3050 # port that another Pod / container could connect in order to get access to target container targetPort: 3000 # port of target container that is exposed nodePort: 31515 # port truly exposed to outside world, which we can use to connect to target container (always ranges between 30000 - 32767, random number in this range is assigned as defaulf if this is not specified) selector: component: web # Service looks for this key-value pair among all objects metadata, and forwards the request to that object for the above specified ports.Sample deployment config

apiVersion: apps/v1kind: Deploymentmetadata: name: client-deploymentspec: replicas: 1 # number of different pods the deployment is supposed to create / maintain selector: # similar to "selector" in service configuration matchLabels: # Deployment gains control over objects having these labels component: web template: # it specifies the configuration used for every single pod that is created / maintained by this deployment metadata: labels: component: web spec: containers: - name: client image: someuser/multi-client ports: - containerPort: 3000Sample ClusterIP service config

apiVersion: v1kind: Servicemetadata: name: client-cluster-ip-servicespec: type: ClusterIP selector: component: web ports: - port: 3000 # other objects in the cluster access the service using this port targetPort: 3000 # port on the target pod that the service is providing access toKubernetes Deployment Methods

2 ways of deployments (Kubernetes supports both of them):

- Imperative deployments - "Do exactly these steps to arrive at this container setup". Implicitly specify each step that should be taken for the deployment. Example: running kubectl commands to update some nodes to run the latest version of an image

- Declarative deployments - "Our container setup should look like this, make it happen". Specify requirements at a high level and let the service handle the rest. Example: updating kubernetes config files to tell master to handle updation of some nodes to a new version of an image.

Kubernetes Github repo issue #33664 - issue with making deployment file to force deployment to update all pods without changing image name or image tag. The problem with Deployment is there is no indicator for container image version that mentions that pods need to be deployed again where the same image has changed. kubectl apply will reject the config file if there are no changes (even if the image has been changed in the container registry). There are 3 ways to solve this issue:

- Manually delete pods to get the Deployment to recreate them with the latest version (not recommended, as it could lead to deletion of wrong pods in production)

- Tag built images with a real version number and specify that version in the config file, which just adds an extra step in the production deployment process

- Use an imperative command to update the image version the Deployment should use (most reasonable of the three). Example: tag the image with a version number (and push it to container registry), then run

kubectl set image <object-type>/<object-name> <container-name>=<new-image-to-use>which changes the "image" property of an object (like Deployment) by specifying the container name that should be updated along with the full name of new image to be used for the container. Here, this command would be:kubectl set image deployment/client-deployment client=someuser/multi-client:v5.

When minikube is installed, there are 2 Docker client-server pairs running in the local environment: one for Docker (if it was installed prior), and the other pair created by minikube within VM (Node). If we want to configure our local Docker CLI client to communicate with Docker servier within minikube VM, use eval $(minikube docker-env) which temporarily configures the Docker CLI to connect to Docker server inside Kubernetes Node temporarily (until the end of terminal session). This can be used for debugging, manually killing containers inside Kubernetes Node and also delete cached images in the Node.

It is possible to combine multiple config files into a single file, and there is no limit to the number of config pieces that can be put into a file. All configs within a file are separated by --- which indicates the separator. Recommended approach is to keep every config in a separate file to identify objects easily.

Persistent Volume Claim (PVC)

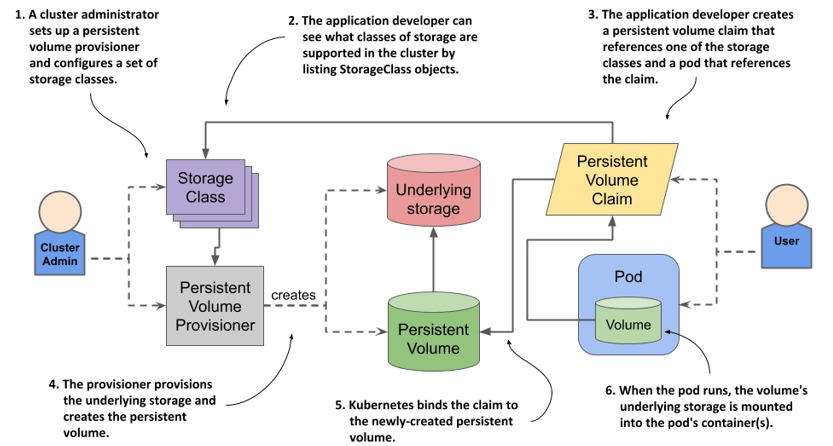

When Postgres is deployed as a container, if the container crashes for any reason and is restarted, all data stored will be wiped out. We can make use of volumes to have a consistent file system that can be accessed by a database (such as Postgres) running on containers. In such cases, the database writes all data to volumes instead of container filesystem. It is not recommended to have multiple replicas of the same database container to access the same volume.

A Volume in Kubernetes represents an object that allows a container to store data at the pod level, and it is not equivalent to a Docker Volume. It is like a data storage pocket that is tied to a specific Pod. Volumes in a Pod can be accessed by any container inside the Pod. There is a limitation: if the Pod dies, then all the volumes tied to the Pod get erased as well, and they would be re-created by Deployment along with other objects. In Kubernetes, volumes are not really appropriate to store data for a database.

In addition to Volumes, there are 2 other types of data storage mechanisms in Kubernetes: Persistent Volume Claim and Persistent Volume. Persistent Volumes are a kind of long term durable storage that are not tied to any specific Pods / containers. They are separate from the Pod, unaffected by any changes in the Pod.

Persistent Volume Claims advertise / specify all available Persistent Volume options inside a cluster (like options displayed on a billboard). We can create config files which list down all these options that Persistent Volume Claims can showcase to all different objects inside the cluster. They are like an advertisement that display available Volume options.

When we request for a Persistent Volume considering the available Claims using Pod config files, Kubernetes consults the list of readily available Persistent Volumes (created ahead of time - statically provisioned), and provides the volume which can be attached to the Pod. Otherwise it creates Persistent Volumes on-the-fly (referred to as dynamically provisioned) based on request. Persistent Volume Claim Configs are attached to Pod config files. Kubernetes tries to find suitable Persistent Volume matching the config, or creates one if not found.

Sample Persistent Volume Claim Config

apiVersion: v1kind: PersistentVolumeClaimmetadata: name: somedb-pvcspec: accessModes: - ReadWriteOnce resources: requests: storage: 2Gi# storageClassName - can be used to explicitly mention storage class to be used

---# above config can be used in deployment file like this, which gets allocated by Kubernetes and assigned to specified container# ....spec: volumes: - name: postgres-storage persistentVolumeClaim: claimName: somedb-pvc containers: - name: postgres image: postgres ports: - containerPort: 5432 volumeMounts: - name: postgres-storage mountPath: /var/lib/postgresql/data # designates where inside the container this storage should be made available subPath: postgres # specifies that any data inside the container that is stored in mountPath should be stored in a folder called "postgres" in the actual PVCThere are 3 different access modes:

- ReadWriteOnce - can be read and written to by a single node

- ReadOnlyMany - can be read by multiple nodes

- ReadWriteMany - can be read and written to by multiple nodes at the same time

Environment variables are defined in spec using env keyword. Each variable is defined using name and value attributes. Usually, the cluster IP service names of databases (defined in their metadata) would form the HOST variables in other services (example: PG_HOST). Environment variables should always be provided as strings.

Secrets

A Secret is a type of Kubernetes object which securely stores a piece of information in the cluster, such as a database password. To create a secret, use the following imperative command:

kubectl create secret generic <secret-name> --from-literal key=value, where generic represents secret type, --from-literal represents that secret is provided in this command instead of a file. The other secret types are docker-registry and tls. Multiple key-value pairs can be added in this command. kubectl get secrets lists all secrets created in a cluster.

Example: kubectl create secret generic postgrespassword --from-literal PGPASSWD=something

This is used in config files like this:

# ...spec: containers: - name: someserver env: - name: REDIS_HOST value: redis-cluster-ip-service - name: PGPASSWORD valueFrom: secretKeyRef: name: postgrespassword key: PGPASSWD# ...Kubernetes networking

Every Pod in a cluster gets its own unique cluster-wide IP address. This means we do not need to explicitly create links between Pods and we almost never need to deal with mapping container ports to host ports. This creates a clean, backwards-compatible model where Pods can be treated much like VMs or physical hosts from the perspectives of port allocation, naming, service discovery, load balancing, application configuration, and migration.

Kubernetes imposes the following fundamental requirements on any networking implementation (barring any intentional network segmentation policies):

- pods can communicate with all other pods on any other node without NAT

- agents on a node (e.g. system daemons, kubelet) can communicate with all pods on that node

Note: For those platforms that support Pods running in the host network (e.g. Linux), when pods are attached to the host network of a node they can still communicate with all pods on all nodes without NAT.

Kubernetes IP addresses exist at the Pod scope - containers within a Pod share their network namespaces - including their IP address and MAC address. This means that containers within a Pod can all reach each other's ports on localhost. This also means that containers within a Pod must coordinate port usage, but this is no different from processes in a VM. This is called the "IP-per-pod" model.

LoadBalancer - is another type of Kubernetes Service which is an old way of getting network traffic into a cluster. Ingress service is the new method of setting up incoming network into the cluster. A LoadBalancer allows access to one specific set of pods in our application only. Kubernetes also configures cloud provider-specific load balancer setups when this is initialized, and connects them to the cluster.

Ingress - a Kubernetes Service which exposes a set of services to the outside world and allow users to access all the pods configured in the cluster. There are several different implementations of Ingress. Nginx Ingress is one of them, which is a community-led project (ingress-nginx) and frequently used. Another implementation available is kubernetes-ingress, which is led by the company Nginx. Setup of ingress-nginx varies depending on the environment (local / cloud provider). The Ingress config files describe a set of routing rules to take incoming traffic and send it to the correct services inside the cluster. When these files are provided to kubectl, it creates an ingress controller, which creates a pod running Ngnix containing a particular set of rules based on the configuration provided. The ingress controller watches for changes to ingress config files and updates the pod that handles incoming traffic. In the case of ingress-nginx, both of these (ingress-controller and pod handling incoming traffic) are the same.

In Google Cloud, the setup consists of a cloud-native load balancer which forwards incoming traffic to a LoadBalancer service connected to a Deployment based on Ingress Config file (which deploys nginx-controller/nginx pod based on config rules). The Nginx pod is responsible for routing traffic to appropriate services inside the cluster. Also, another Deployment is set up, called default backend (Pod with ClusterIP service). The default backend is used for a series of healthchecks to make sure the cluster is up and running. Ideally the default backend would be replaced with backend server (Express, FastAPI etc.).

The nginx-controller/nginx image is used for the pod connected to LoadBalancer service instead of default nginx image. This is because the image has additional configuration to operate inside Kubernetes clusters, like routing incoming traffic to the pods directly instead of ClusterIP services to allow for features like sticky sessions etc. The ingress service automatically listens on ports 80 and 443. The Nginx configuration by default chooses HTTPS connection using a dummy certificate.

Sample Ingress config:

apiVersion: extensions/v1beta1kind: Ingressmetadata: name: ingress-service annotations: # they are additional configuration options that specify higher level setup around the created ingress object. kubernetes.io/ingress.class: nginx # creates ingress-controller based on nginx project nginx.ingress.kubernetes.io/rewrite-target: / # remove additional route urls after / before sending the request to pods. Example: it rewrites /api to /spec: rules: - http: paths: # requests should be routed to the following paths - path: / backend: serviceName: client-cluster-ip-service servicePort: 3000 - path: /api/ backend: serviceName: server-cluster-ip-service servicePort: 5000Why Google Cloud is preferred for Kubernetes than AWS

Google created Kubernetes - the open source project and financially supported it for the first few years of its existence. AWS got Kubernetes support in early 2018. Google Cloud offers "cloud console" - a terminal connected to all resources hosted there which also provides access to a kubectl-like tool connected to production Kubernetes instance. Documentation for Kubernetes in Google Cloud is much better compared to AWS.

Things to note in GKE console

Node configuration (node pool) displayed in the console describes specifications of each different virtual machine that will be added to Kubernetes Cluster as a Node. The default storage class is standard with a provisioner of kubernetes.io/gce-pd. GKE enables RBAC by default. Role Based Access Control (RBAC) limits who can access and modify objects in Kubernetes cluster. RBAC terminologies in a Kubernetes Cluster:

- User Accounts identify a person administering the Kubernetes cluster

- Service Accounts identify a pod administering the cluster

- ClusterRoleBinding authorizes an account (user / service) to do a certain set of actions across the entire cluster

- RoleBinding authorizes an account to do a certain set of actions in a "single namespace"

Helm and cert-manager

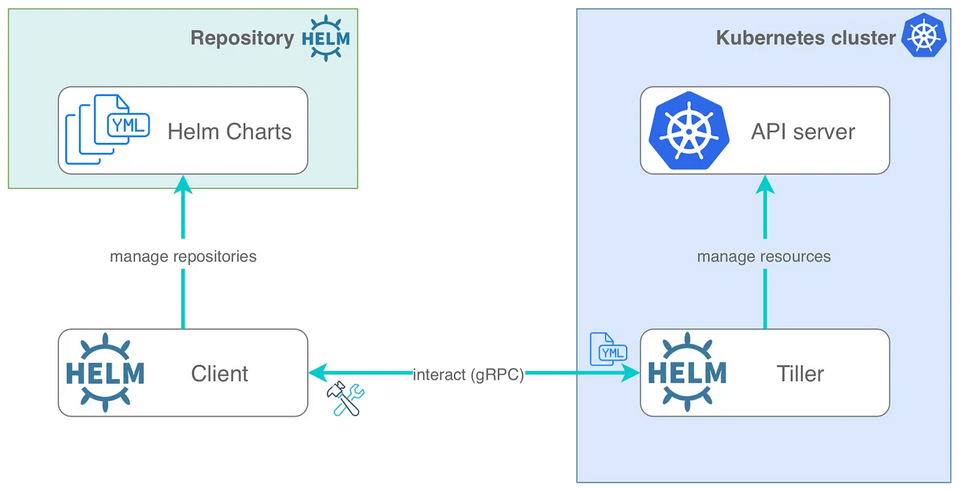

Helm is a program that we can use to install and administer third-party software inside the Kubernetes cluster. When Helm is installed, Helm Client (CLI tool) and Tiller Server are installed as part of it. Tiller is a server pod running inside the Kubernetes cluster, which is responsible for modifying the cluster to install additional programs in it. After installing tiller and assigning proper permissions, initialize it by using helm init --service-account tiller upgrade.

kubectl create serviceaccount --namespace kube-system tiller- creates a new service account named tiller in the kube-system namespacekubectl create clusterrolebinding tiller-cluster-rule --clusterrole=cluster-admin --serviceaccount=kube-system:tiller- creates a new clusterrolebinding with the (pre-defined) rolecluster-adminand assign it to service account tiller

cert-manager adds certificates and certificate issuers as resource types in Kubernetes clusters, and simplifies the process of obtaining, renewing and using those certificates. It can issue certificates from a variety of supported sources, including Let's Encrypt, HashiCorp Vault, and Venafi as well as private PKI. It will ensure certificates are valid and up to date, and attempt to renew certificates at a configured time before expiry. The ingress service should be updated once the certificates are retrieved.

cert-manager is installed via Helm, which installs certain Kubernetes objects via a Deployment, creating certain Pods, Service Account and Cluster Role Bindings. In addition to this, the following objects need to be installed:

- Certificate - object describing details about the certificate that should be obtained. It is linked to a Secret once the certificate is retrieved.

- Issuer - object telling cert-manager where to get the certificate from (a certificate authority)

Sample config file for Issuer:

apiVersion: certmanager.k8s.io/v1alpha1kind: ClusterIssuermetadata: name: letsencrypt-prod # can be named after the source of the issuerspec: acme: server: https://acme-v02.api.letsencrypt.org/directory # link to the api to setup issuer communication email: "abc@abc.com" privateKeySecretRef: name: letsencrypt-prod http01: {} # basically specifies that we want to use http process for getting a certificateSample config file for Certificate:

apiVersion: certmanager.k8s.io/v1alpha1kind: Certificatemetadata: name: k8s-sample-com-tlsspec: secretName: k8s-sample-com # can be anything; specifies where the certificate should be stored after it is obtained by cert-manager issuerRef: # reference to the Issuer that is already set up name: letsencrypt-prod kind: ClusterIssuer commonName: k8s-sample.com # domain name dnsNames: # list of all different domains that should be associated with the certificate - k8s-sample.com - www.k8s-sample.com acme: config: - http01: ingressClass: nginx domains: # list of all domains that should go through verification process - k8s-sample.com - www.k8s-sample.comSkaffold

Skaffold is a command-line tool completely separate from Kubernetes which facilitates local development. It watches local directory for changes and update that in Kubernetes cluster using one of the following methods:

- Rebuilding client image from scratch and then updating Kubernetes cluster

- Injecting updated files into the Client pod and rely on the application to automatically update itself

Sample Skaffold config file:

apiVersion: skaffold/v1beta2kind: Configbuild: # lists out all different deployments that should be managed by Skaffold local: push: false # by default Skaffold pushes built image to DockerHub, which can be disabled like this artifacts: - image: someuser/multi-client context: client # folder where the Docker image will be built docker: dockerfile: Dockerfile.dev sync: # series of matching file paths that informs Skaffold to watch for changes and sync them without rebuilding the image "**/*.js": . "**/*.css": . "**/*.html": . - image: someuser/multi-server context: server docker: dockerfile: Dockerfile.dev sync: "**/*.js": . - image: someuser/multi-worker context: worker docker: dockerfile: Dockerfile.dev sync: "**/*.js": .deploy: kubectl: manifests: # all Kubernetes config files that should be managed by Skaffold - k8s/client-deployment.yaml - k8s/server-deployment.yaml - k8s/worker-deployment.yaml - k8s/server-cluster-ip-service.yaml - k8s/client-cluster-ip-service.yamlSkaffold falls back to 1st method (rebuilding image from scratch) whenever any file which isn't specified in the config gets changed. It can be started by using skaffold dev. It automatically creates and deletes all Kubernetes resources specified in the config file when it is started and shutdown. It can also handle Kubernetes resources in its configuration that are already up and running.